Since I do festivals every year, along with a couple of other camping trips if the weather is good enough, I’ve been taking equipment with me for years in flight cases to make things more comfortable. Things like a large battery to power lights & device charging, an old Eberspacher diesel heater for the times when the weather isn’t great, and an inverter to run the pumps built into airbeds.

Red Diesel / Heating Oil is my fuel of choice for camping purposes, as it’s about the safest fuel around, unlike Butane/LPG it is not explosive, will not burn very readily unless it’s atomized properly & it’s very cheap. Paraffin is an alternative fuel, but it’s expensive in the UK, at about £12 per 5L.

The Hexamine-based tablet fuels the UK festivals promote is nasty stuff, and the resulting combustion products are nastier still. (Things like Hydrogen Cyanide, Formaldehyde, Ammonia, NOX). They also leave a sticky black grok on every cooking pot that’s damn near impossible to remove. Meths / Trangia stoves are perfectly usable, but the flame is totally invisible, and the flammability of alcohol has always made me nervous when you’ve got a small pot of the stuff boiling while it’s in operation in the middle of a campsite filled with sloshed festival goers. A single well-placed kick could start a massive fire.

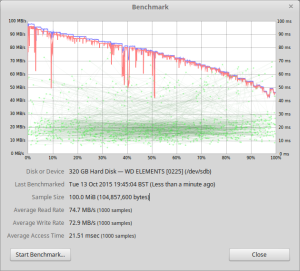

Over the years the gear has evolved and grown in size, so I decided building everything into one unit on wheels would be the best way forward. I’ve been working on this for some time, so it’s time to get some of the details on the blog! Above you can see the system used for last year’s camping, the heater is separate, with a 25L drum of heating oil, the battery is underneath the flight case containing all the power components, and it’s currently charging All The Things.

Above is the new unit almost finished, the bottom frame is a standard eBay-grade 4-wheel trolley with a few modifications of my own, with a new top box built from 12mm hardwood marine plywood. This top is secured in place with coach bolts through the 25mm angle iron of the trolley base. The essential carbon monoxide detector is fitted at the corner.

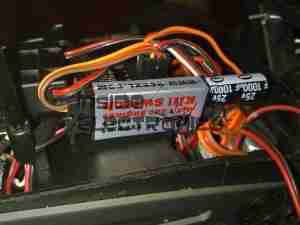

The inside gets a bit busy with everything crammed in. The large Yuasa 200Ah lead-acid battery is at the far end, with it’s isolation switch. Right in the middle is the Eberspacher heater with it’s hot air ducting. I’ve fitted my usual 12/24v dual voltage system here, with the 24v rail generated from a large 1200W DC-DC converter.

The hot air duct for the heater is fed out through a standard vent in the front. Very handy for drying out after a wet day.

Here’s a closeup of the distribution bus bars, with both negative rails tied together in the centre to keep the positives as far away from each other as possible, to reduce the possibility of a short circuit between the two when working on the wiring. The EpEver Tracer 4210A MPPT Solar Charge Controller is on the left, tucked into the corner. This controller implements the main circuit protection for the battery, having a 40A limit. Individual circuits are separately fused where required. Solar input on this unit is going to be initially provided by a pair of 100W flexible panels in series for a 48v solar bus, the flexible panels are essential here as most of the festivals I attend do not allow glass of any kind onsite, not to mention the weight of rigid panels is a pain.

I’ve stuck with the 3-pin XLR plugs for power in this design, giving both the 12v rail, 24v rail & ground.

Tucked under the DC outputs are a pair of panel sockets for the 600W inverter. This cheapo Maplin unit is only usually used to pump up air beds, so I’m not expecting anyone to pull anything near max output, but a warning label always helps.

Behind the front panel is the hardwiring for the power sockets. The DC jacks are connected together using 2mm solid copper wire, bent into bus bars.The mains wiring underneath is a simple radial circuit straight from the inverter. The large cylinder on the left is a hydraulic pump from a BMW Z3, which runs a hydraulic cylinder for lifting the lid of the top box, used simply because I had one in the box of junk.

External fuelling is dealt with by a small gear pump, this is used to fuel up the Optimus Stove & Petromax Lantern. This is in fact a car windscreen wash pump, but it has coped well with pumping hydrocarbons, it currently has a small leak on the hose connections, but the seals are still entirely intact.

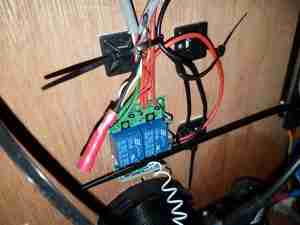

There’s a small remote relay module here, for switching the DC output for lighting & the heater from afar. Very useful when it’s dark, since there’s no need to fumble around looking for a light switch. A car-style fob on my keyring instead.

Since the Eberspacher 701 controller I have is an ex-BT version, it’s very limited in it’s on time, a separate timeswitch is fitted to control the heater automatically. Being able to return to a nice warm tent is always a bonus.

Just to the left can be seen the top ball joint for the hydraulic cylinder that lifts the top of the box.

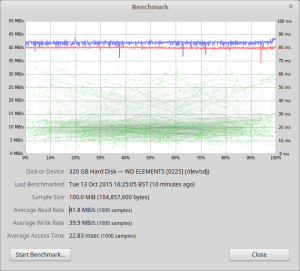

The final large component is the battery charger. This unit will maintain the battery when the trolley isn’t being used.

On the left side is the old Atom motherbaord used to provide a 4G router system. This unit gets it’s internet feed from a UMTS dongle & provides a local WiFi network for high speed connectivity. The bottom of the hydraulic cylinder is visible in the bottom right corner.

Since the Eberspacher obviously needs fuel, a tank was required. In previous years I’ve used jerry cans for this purpose, but this trolley is supposed to have everything onboard, for less setup time. The tank is constructed from 3mm steel plate, MIG welded together at the seams to create a ~40L capacity. The filler neck is an eBay purchase in Stainless Steel. No photos of the tank being welded together, as I was aiming to beat sunset & it’s very difficult to operate a camera with welding gauntlets on 😉

The tank is the same width as the trolley frame, so some modification was required, having the wheels welded directly to the sides of the tank. This makes the track wider at the rear, increasing stability.

A quick view inside the tank through the level sender port shows the copper dip tubes for fuel supply to the heater, and an external fuel hose for my other fuel-powered camping gear. These tubes stop about 10mm from the bottom of the tank to stop any moisture or dirt from being drawn into the pumps.

The top of the tank is drilled for the fuel fittings & the level sender and has already been painted here. The 1mm base plate has yet to be painted.

Touching up the paint & fitting the sender is the last job for this part. The mesh bottom of the trolley has been replaced by a 1mm steel sheet to support the other parts, mainly the heater. Fuel lines are run in polyurethane tubing to the fuel pumps.

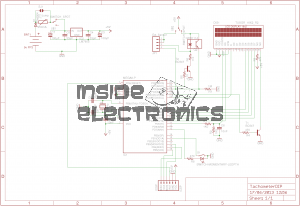

All the instruments & controls are on a single panel, with the Eberspacher thermostat, external fuelling port & pump switch, inverter control, the solar controller monitor panel, cover buttons, router controls, compressed air & fuel gauges.

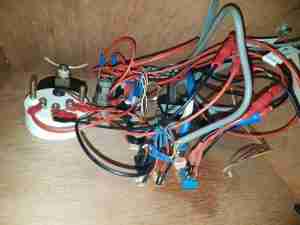

As is usual behind instrument panels, there’s a rat’s nest of wiring. There’s still the pressure gauge to connect up for the compressed air system, and the nut on one of the router buttons is such a tight fit I’ve not managed to get it into place yet.

The support components for the Eberspacher heater are mounted underneath the baseplate, with the fuel dosing pump secured to a rail with a pair of cable ties, and some foam tape around to isolate the constant clicking noise these pumps create in operation. The large black cylinder is the combustion air intake silencer, with the stainless steel exhaust pipe to the left of that. Silencing these heaters is essential – they sound like a jet engine without anything to deaden the noise. Most of this is generated from the side-channel blower used in the burner.

Bolted to the underside are a pair of exhaust silencers, one is an Eberspacher brand, the other is Webasto, since the latter type are better at reducing the exhaust noise. Connections are sealed with commerical exhaust assembly paste, the usual clamps supplied do not do a good enough job of stopping exhaust leaks.

Next update to come when I get the parts in for the air compressor system.