In a word, no they aren’t any good. As usual, cheap doesn’t equal good, and in this case the cheapo clones are a total waste of money. Read on for the details!

I’ve been looking into using a cheap Chinese clone Honda GX35 engine to drive an automotive alternator as a portable battery charging & power unit. These engines are available very cheaply on eBay, aimed at the mini-bike/go-kart market.

For those not in the know, the Honda GX25/35 4-strokes are strimmer-type engines that traditionally were always of 2-stroke construction. Honda worked out how to have a wet-sump engine without the need to keep the engine always in the “upright” position. They do not require mixing of oil into the fuel for lubrication as 2-strokes do, so should be much cleaner running.

So far I’ve had two of these cheap engines, as the first one died after only 4 hours run time, having entirely lost compression. At the time the engine was idling, no load, having been started from cold only a few minutes before. Having checked the valve clearances to make sure a valve wasn’t being held partially open, I deduced that the cause was broken piston rings. This engine was replaced by the seller, so I didn’t get a chance to pull it to bits to find out, but I decided to do a full teardown on the replacement to see where the cloners have cut corners.

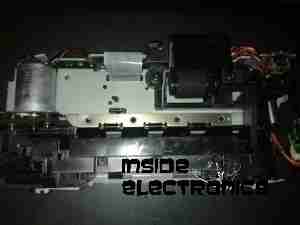

I’ve already stripped off the ancillary components: exhaust, carburettor, fuel tank, cowlings, as these parts are standard to any strimmer engine. The large black hose here is the oil return feed back to the rocker cover from the crankcase. The oiling system in these engines is rather clever. The main engine block is made of light alloy, probably some permutation of Aluminium. There is much flashing left behind between the cylinder fins from the die-casting process, and not a single engine manufacturer’s logo anywhere. (From what I’ve read, the genuine Honda ones have their logo on the side of the crankcase).

Here’s the top of the engine with valves, rockers & camshaft. All the valve gear up here, minus the valves themselves & springs, are manufactured from sintered steel, there are no proper “bearings”, the steel shafts just run in the aluminium castings. The cam gear is of plastic, with the sintered steel cam pressed into place. The cam also has the bearing surface for the pin that the whole assembly rotates on. The timing belt runs in the oil & is supposed to last the life of the engine, and while I’d believe that in the original Honda, I certainly wouldn’t in this engine. The black grommet is the opening of the oil return gallery.

Here’s the cam on the back of the plastic pulley. A single cam is used for both intake & exhaust valves for space & simplicity.

Just visible under the intake valve spring is a simple stem seal, to hopefully prevent oil being sucked down the valve guide into the cylinder by intake vacuum. Running these cheap engines proves this seal to be ineffective, as they blow about as much blue oil smoke as a 2-stroke when they’re started cold. 😉

The starter side is where the oil sump is located on these engines, along with the dipstick.

The flywheel end of the engine is the usual fare for small engines. Ignition is provided by a magneto, with a magnet in the flywheel. This is no different from the 2-stroke versions. As these ignitions fire on every revolution of the crankshaft, the spark plug fires both on compression, igniting the fuel for normal operation, and again into the exhaust stroke, where the spark is wasted.

One thing I have noticed about these engines is an almost total lack of cooling air coming through the cowling over the cylinder cooling fins. Plenty was flowing over the exhaust silencer side, I believe bad housing design would be what causes this problem. A lack of cooling certainly wouldn’t help engine longevity!

Separating the bottom of the engine was a little difficult, as there is a significant bead of sealant used instead of a gasket. Inside the sump of the engine are a pair of paddles, which stir up the oil into a mist. As the piston moves in the cylinder, it acts as a pump, creating alternating pulses of pressure & vacuum in the crankcase. Oil mist flows through a drilling in the crank from the sump, into the crankcase where it (hopefully) lubricates the bearings & the cylinder wall. Incidentally, the only main bearings are on the crankcase – the far end of the shaft that carries the oil paddles & timing belt is just flapping in the breeze, the only support being the oil seal in the outer housing. The crank itself isn’t hardened – a file easily removes metal from all parts that I could get at. The big end journal pin might be, but these cranks are pressed together so I can’t access that part.

The oil mist feeds into the crankcase through this hollow section of shaft, there’s a drilling next to the timing belt pulley to connect the two spaces together.

The lower crankcase is just a simple die casting, there’s a check valve at the bottom under the crankshaft to transfer oil to the rocker cover, through the rubber tube on the outside of the engine. After the oil reaches the rocker box, it condenses & returns to the sump via the timing belt cavity.

Removing the crankshaft from the engine block gives me a look at the piston. The factory couldn’t even be arsed to machine the crown, it’s still got the rough finish from the hot-forging press. This bad finish will pick up much carbon from combustion, and would probably cause detonation once enough had accumulated to become incandescent in the heat of combustion. Only the centre is machined, just enough for them to stamp a number on.

A look up the cylinder bore shows the valves in the cylinder head. These engines, like their 2-stroke cousins have a single casting instead of a separate block & head, so getting at the valves is a little more of a pain. The cylinder bore itself is a cast-in iron liner and it’s totally smooth – like a mirror finish. There’s not a single sign of a crosshatch pattern from honing. If the first engine that died on me was the same – I’d be surprised if it wasn’t, this could easily cause ring breakage. The usual crosshatch pattern the cylinder hone produces holds oil, to better help lubricate the piston & rings. Without sufficient lubrication, the rings will overheat & expand far enough to close the end gap. Once this happens they will break.

Finally, here’s the valves with their springs removed from the cylinder. These are the smallest poppet valves I’ve ever seen, a British penny is provided for scale.

In all, these engines share many components with the older 2-stroke versions. The basic crankshaft & connecting rod setup is the same as I’ve seen in many old 2-strokes previous, the addition of the rather ingenious oiling system by Honda is what makes these tiny 4-strokes possible. I definitely won’t be trusting these very cheap copies in any of my projects, reliability is questionable at the least. The apparent lack of cooling air flow over the cylinder from the flywheel fan is concerning, along with the corner-cutting on the cylinder finishing process & piston crown, presumably to reduce factory costs.